In physics and thermodynamics, heat is energy transferred from one body, region, or thermodynamic system to another due to thermal contact when the systems are at different temperatures. It is also often described as one of the fundamental processes of energy transfer between physical entities. In this description, it is an energy transfer to a body in any other way than due to work.[1]

In engineering, the discipline of heat transfer classifies energy transfer in or between systems resulting in the change of thermal energy of a system as either thermal conduction, first described scientifically by Joseph Fourier, by fluid convection, which is the mixing of hot and cold fluid regions due to pressure differentials, by mass transfer, and by thermal radiation, the transmission of electromagnetic radiation described by black body theory.

Thermodynamically, energy can only be transferred as heat between objects, or regions therein, with different temperatures, as described by the zeroth law of thermodynamics. This transfer happens spontaneously only in the direction to the colder body, as per the second law of thermodynamics. The transfer of energy by heat from one object to another object with an equal or higher temperature can happen only with the aid of a heat pump via mechanical work, or by some other similar process in which entropy is increased in the universe in manner that compensates for the decrease of entropy in the cooled object, due to the removal of the heat from it. For example, heat may be removed against a temperature gradient by spontaneous evaporation of a liquid.

A related term is thermal energy, loosely defined as the energy of a body that increases with its temperature. Thermal energy is also sometimes referred to as heat, although the definition of heat requires it to be in transfer between two systems.

Contents |

[edit] Overview

Heat flows spontaneously only from systems of higher temperature to systems of lower temperature. When two systems come into thermal contact, they always exchange thermal energy due to the microscopic interactions of their particles. When the systems are at different temperatures, the net flow of thermal energy is not zero and is directed from the hotter region to the cooler region, until their temperatures are equal and the flow of heat seizes. At this point they obtain a state of thermal equilibrium, exchanging thermal energy at an equal rate in both directions.

The first law of thermodynamics states that the energy of an isolated system is conserved. Therefore, to change the energy of a system, energy must be transferred to or from the system. For a closed system, heat and work are the only two mechanisms by which energy can be transferred. Work performed on a system is, by definition [1], an energy transfer to the system that is due to a change to external parameters of the system, such as the volume, magnetization, center of mass in a gravitational field. Heat is the energy transferred to the system in any other way.

In the case of systems close to thermal equilibrium where notions such as the temperature can be defined, heat transfer can be related to temperature difference between systems. It is an irreversible process that leads to the systems coming closer to mutual thermal equilibrium.Human notions such as hot and cold are relative terms and are generally used to compare one system’s temperature to another or its surroundings.

[edit] Definitions

Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell, in his 1871 classic Theory of Heat, was one of the first to enunciate a modern definition of heat. Maxwell outlined four stipulations for the definition of heat:

- It is something which may be transferred from one body to another, according to the second law of thermodynamics.

- It is a measurable quantity, and thus treated mathematically.

- It cannot be treated as a substance, because it may be transformed into something that is not a substance, e.g., mechanical work.

- Heat is one of the forms of energy.

- The energy transferred from a high-temperature system to a lower-temperature system is called heat.[2]

- Any spontaneous flow of energy from one system to another caused by a difference in temperature between the systems is called heat.[3]

[edit] Notation and units

As a form of energy heat has the unit joule (J) in the International System of Units (SI). However, in many applied fields in engineering the British Thermal Unit (BTU) and the calorie are often used. The standard unit for the rate of heat transferred is the watt (W), defined as joules per second.

The total amount of energy transferred as heat is conventionally written as Q for algebraic purposes. Heat released by a system into its surroundings is by convention a negative quantity (Q < 0); when a system absorbs heat from its surroundings, it is positive (Q > 0). Heat transfer rate, or heat flow per unit time, is denoted by .

.

[edit] Semantic misconceptions

There is some debate in the scientific community regarding exactly how the term heat should be used.[5] In current scientific usage, the language surrounding the term can be conflicting and even misleading. One study showed that several popular textbooks used language that implied several meanings of the term, that heat is the process of transferring energy, that it is the transferred energy, i.e., as if it were a substance, and that is an entity contained within a system, among other similar descriptions. The study determined it was not uncommon for a combination of these representations to appear within the same text.[6] They found the predominant use among physicists to be that if it were a substance.In a 2004 lecture, Friedrich Herrmann mentioned that the confusion may result from the modern practice of defining heat in terms of energy, which is at odds both with the historic scientific definitions and with the modern lay concept of heat. He argues that the quantity heat as introduced by Joseph Black in the 18th century, and as used extensively by Sadi Carnot, was in fact what is today known as entropy-- something possessed by a substance in amounts related to that substance's temperature and mass, which exits one substance and enters another in the presence of a temperature gradient and can be created in many ways but never destroyed. He further argues that the layperson's concept of heat is also essentially this entropy concept, and so in re-defining heat to refer to an energy concept, modern science creates an unnecessarily awkward and confusing presentation of thermal physics. [7]

[edit] Internal energy and enthalpy

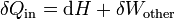

In the case where the number of particles in the system is constant, the first law of thermodynamics states that the differential change in internal energy dU of a system is given by the differential heat flow δQ into the system minus the differential work δW exerted by the system:[note 1]

,

,

,

,

,

,

is equal to the differential enthalpy change (dH) of the system. Substitution gives:

is equal to the differential enthalpy change (dH) of the system. Substitution gives: ,

,

Both enthalpy, H, and internal energy, U, are state functions. In cyclical processes, such as the operation of a heat engine, state functions return to their initial values. Thus, the differentials for enthalpy and energy are exact differentials, which are dH and dU, respectively. The symbol for exact differentials is the lowercase letter d.

In contrast, neither Q nor W represents the state of the system (i.e. they need not return to their original values when returning to same step in the following cycle). Thus, the infinitesimal expressions for heat and work are inexact differentials, δQ and δW, respectively. The lowercase Greek letter delta, δ, is the symbol for inexact differentials. The integral of any inexact differential over the time it takes to leave and return to the same thermodynamic state does not necessarily equal zero. However, for processes involving no change in volume (i.e. dV = 0), applied magnetic field, or other external parameters (i.e. δWout = 0 and δWin = 0), δQ forms the exact differential,  , wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:- dU = TdS = δQrev.

Likewise, for an isentropic process (i.e. δQ = 0 and dS = 0), δW forms the exact differential,  , wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:

, wherein the following relation applies:- dU = − pdV = − δWrev,

[edit] Path-independent examples for an ideal gas

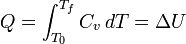

For a simple compressible system such as an ideal gas inside a piston, the internal energy change ΔU at constant volume and the enthalpy change ΔH at constant pressure are modeled by separate heat capacity values, which are Cv and Cp, respectively.

Constrained to have constant volume, the heat, Q, required to change its temperature from an initial temperature, T0, to a final temperature, Tf, is given by this formula:[edit] Incompressible substances

For incompressible substances, such as solids and liquids, the distinction between the two types of heat capacity (i.e. Cp which is based on constant pressure and Cv which is based on constant volume) disappears, as no work is performed.

[edit] Latent and sensible heat

In a 1847 lecture entitled On Matter, Living Force, and Heat, James Prescott Joule characterized the terms latent heat and sensible heat as components of heat each effecting distinct physical phenomena, namely the potential and kinetic energy of particles, respectively.[8] He described latent energy as the energy of interaction in a given configuration of particles, i.e. a form of potential energy, and the sensible heat as an energy affecting the thermal energy, which he called the living force.

Latent heat is the heat released or absorbed by a chemical substance or a thermodynamic system during a change of state that occurs without a change in temperature. Such a process may be a phase transition, such as the melting of ice or the boiling of water.[9][10] The term was introduced around 1750 by Joseph Black as derived from the Latin latere (to lie hidden), characterizing its effect as not being directly measurable with a thermometer.

Sensible heat, in contrast to latent heat, is the heat exchanged by a thermodynamic system that has as its sole effect a change of temperature.[11] Sensible heat therefore only increases the thermal energy of a system.[edit] Specific heat

Specific heat, also called specific heat capacity, is defined as the amount of energy that has to be transferred to or from one unit of mass (kilogram) or amount of substance (mole) to change the system temperature by one degree. Specific heat is a physical property, which means that it depends on the substance under consideration and its state as specified by its properties.

The specific heats of monatomic gases (e.g., helium) are nearly constant with temperature. Diatomic gases such as hydrogen display some temperature dependence, and triatomic gases (e.g., carbon dioxide) still more.[edit] Entropy

Main article: Entropy

In 1856, German physicist Rudolf Clausius defined the second fundamental theorem (the second law of thermodynamics) in the mechanical theory of heat (thermodynamics): "if two transformations which, without necessitating any other permanent change, can mutually replace one another, be called equivalent, then the generations of the quantity of heat Q from work at the temperature T, has the equivalence-value:"[12][13]

In 1865, he came to define this ratio as entropy symbolized by S, such that, for a closed, stationary system:

and thus, by reduction, quantities of heat δQ (an inexact differential) are defined as quantities of TdS (an exact differential):

In other words, the entropy function S facilitates the quantification and measurement of heat flow through a thermodynamic boundary.

To be precise, this equality is only valid, if the heat δQ is applied reversibly. If, in contrast, irreversible processes are involved, e.g. some sort of friction, then instead of the above equation one hasThis is the second law of thermodynamics.

[edit] Heat transfer in engineering

A red-hot iron rod from which heat transfer to the surrounding environment will be primarily through radiation.

The discipline of heat transfer, typically considered an aspect of mechanical engineering and chemical engineering, deals with specific applied methods by which heat transfer occurs. Note that although the definition of heat implicitly means the transfer of energy, the term heat transfer has acquired this traditional usage in engineering and other contexts. The understanding of heat transfer is crucial for the design and operation of numerous devices and processes.

Heat transfer may occur by the mechanisms of conduction, radiation, and mass transfer. In engineering, the term convective heat transfer is used to describe the combined effects of conduction and fluid flow and is often regarded as an additional mechanism of heat transfer. Although separate physical laws have been discovered to describe the behavior of each of these methods, real systems may exhibit a complicated combination. Various mathematical methods have been developed to solve or approximate the results of heat transfer in systems.

No comments:

Post a Comment